Tiago’s note: this case study is from C. Wess Daniels, a professor of religious studies at Guilford College. It explains how he’s adapted the progressive summarization technique to help undergraduate students learn faster, retain it longer, and preserve their notes for lifelong use.

After learning about Progressive Summarization in Tiago’s Building a Second Brain course I took this past summer, I have been trying to find ways to incorporate it wherever, whenever, and however I possibly can. Tiago’s concept of “designing your notes” so that they are not only interesting to look at, but useful for your future self — balancing the tension between context and discoverability — has already made a huge impact on my research and writing.

I took the course this summer not just for my own professional development and to improve my own Personal Knowledge Management (PKM), but so that I could take some of the ideas I learned back to the classroom. I teach undergraduate religious studies courses at Guilford College in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Before I took Tiago’s course, I would assign daily reading reviews for my students as the bread and butter of their assignments. Over the course of a 15-week semester a student would write 28–30 reviews of various books and articles we covered in class.

These “old style” reading reviews are made up of a set of directed queries:

Journal 300–500 words that include key points, quotes, and your personal questions and reflections on the reading. Continue to connect these readings back to the bigger research questions of the course

And then I’d add a “collaborative” piece like this:

Respond to your classmates’ reviews

This is pretty standard — focus on the stuff that really stands out to you, key quotes, etc. and then interact with your classmates. We use Canvas to allow students to post their reviews in a discussion thread alongside those of their classmates.

The Inaccessibility of a Reading Review in a Comment Thread

After taking Tiago’s course, I couldn’t go back to this earlier method of review. Not only is it uninteresting, but more importantly, it is unhelpful for my students’ future selves. I realized that all those reviews— all their work and thinking about the texts they read — would become almost completely inaccessible to them after my class was over.

Although five years from now they could theoretically find those notes again, it would require remembering which class they read the book in, which semester they took the course, figuring out how to log back into Canvas, digging down into that specific course, and then working through each of the 28–30 class sessions, scrolling through all the comments in hopes of finding that one review they were looking for. You can see I’m not particularly optimistic about this process being successful after a couple semesters, let alone a few years.

I wanted to also build on the assumption that what my students are doing in my class might actually be USEFUL to them in their research for other classes, and perhaps even in their own lives. So why not make the majority of the content from the course — the notes they take for the class — more accessible and useful to their future selves?

Reinterpreting Progressive Summarization for the Classroom

Therefore, I set about translating progressive summarization into a regular practice (and assignment) in my classes. Here is how I went about doing that.

First, before introducing progressive summarization, I have my students write out 7–10 “problems” for the course. That is, when it comes to understanding the specific content of the class (theology, physics, philosophy, etc.), what are the problems or questions they would like to see answered? This is based off of Tiago’s 12 Favorite Problems exercise, in which we come up with large-scale, open-ended questions that can help guide learning and research.

I like this exercise in a classroom, not only because it tells me more about what the student is bringing to the class — and where I might change course to address their questions — but it creates a “clothes hanger,” so to speak, on which my students can hang the ideas from their reading. It provides a framework for resonance that we can keep coming back to throughout the course, and one that they will have a much higher likelihood of returning to long after the course is done.

Second, I teach them how to practice progressive summarization and I explain my adapted version of it for the classroom. You can find the four posts explaining progressive summarization here.

I want to show you exactly what I put into my syllabus, as well as link to from the Canvas course. Here is a link to these instructions in Evernote, with screenshots. I also share with my students an example of a progressively summarized note so that they have an idea of how it will look.

Here is the explanation I include in the class syllabus:

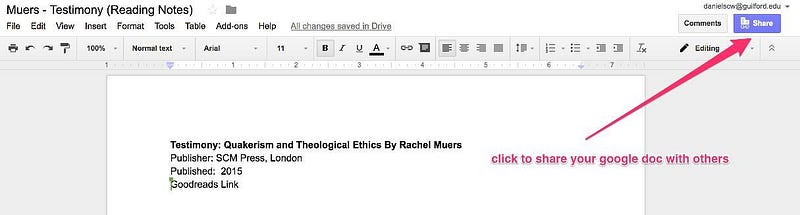

- Create a Google Drive folder for the class (e.g. GST 405…) and then one document per book, article, etc. Title the document (e.g. “Muers — Testimony”). At the top of the document write in the pertinent publishing information, link back to the book on Goodreads or Amazon, or link to an online article on the book so you can find your source later.

- Create a heading (e.g. Chapter 1 “Bearing Witness”) and then add your notes on that chapter.

- Take notes on each source as you read. You are looking for key ideas, critical narratives, important people, themes that stick out, or other connections that seem important. Anything that really resonates with you or greatly challenges your current thinking, especially as it pertains to one of your 10 problems. These notes are for you and your future self. Be sure to give yourself enough context that you know why you thought this was noteworthy in the past.

- After you finish reading the chapter and taking notes, go back through your notes and bold the things that stand out to you now, after having finished the chapter. You are looking to pull out the main points in each paragraph, the brief ideas that you can scan quickly to get the basic gist of the note.

- Share your Google Doc. Go to the course on Canvas and paste a public link for your classmates to read and mark up (make sure when you share the document that it is set so that anyone can comment).

- Read 3 classmates’ notes and for each one highlight 3–5 key points/sections/sentences/words that resonate with you. In the comments section, write a short comment about why you highlighted that portion, or why it resonated with you.

- We do this for the whole book chapter by chapter, and then we go back and write a 300-word summary at the top of our notes for that book, incorporating the “layers” created through this highlighting process.

- Extra credit — for those who do handwritten notes and “sketchnotes” (visual drawings). Please include these in your Google Doc. If you have pictures or images you want to include, use the Google Drive app, your phone’s camera, or an iOS app like Scannable to take a picture of the images and upload them to your Google Doc.

Goals for this project:

- To practice different ways of note-taking that include “progressive summarization” so that you are able to quickly gather key points from your reading

- To get immediate feedback from your classmates

- To give you an artifact you can take with you for other classes at Guilford

- To help you think through what resonates with you, what connects to the questions you find important, and what is relevant to your own thinking and development as a scholar

Results

I have used this in two classes this fall. So far, the students have done incredibly well with it, have really enjoyed learning a new method of note-taking, and I have (anecdotally) noticed the quality of work going up as well.

I believe that this is a very “learner-centered” approach because by using P.S. in the classroom students find their notes become far more useful to them later in the semester. They are more accessible, focused on the ideas they are interested in learning, and quickly scannable for when they study and work on their research papers.

This also allows for the “slow burn” effect of ideas percolating over the course of a whole semester and are easy to come back to and retrieve when needed. If you’re like me and you’ve ever tried to find a note or an idea in a handwritten notebook from a class 20 years ago, you will understand the importance of easy retrieval.

Beyond this, the students leave the class with a set of well-designed, progressively summarized notes, to take with them throughout the rest of their college career and beyond, becoming a highly valuable asset to their ongoing learning.

I’d love to hear comments, feedback, and other ideas or techniques you have incorporated into your teaching as a result of Tiago’s methods.

Follow me on Medium and Twitter at @cwdaniels

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- POSTED IN: Building a Second Brain, Case studies, Curation, Education, Guest Posts, Note-taking