In my time as a reader and writer, I’ve discovered something I didn’t expect: reading multiple books at the same time, or writing multiple essays at the same time, increases not only the quantity of books I read, but also the quality of the essays I write.

As a young reader, I would always read one book at a time. I would start a book, and keep reading it until I had finished it. Very rarely, I would decide to stop reading a book before I had finished it.

I started reading multiple books in parallel while studying at St. John’s College, my alma mater and a Great Books school, where almost all of the school work involves reading books. Reading in parallel dramatically increased the number of books I was able to read in a given time period. I found myself reading at least 100 books a year (including my own personal reading). By reading multiple books at the same time, I was able to discover more quickly if I didn’t want to finish a book, and switch to a new book. Or if I simply needed a break from one book, I could move to another before coming back to the first with fresh eyes. Most importantly, I found myself enjoying reading (even) more, which resulted in me reading more. Since graduating, I’ve maintained the habit of reading in parallel, and consistently read 50+ books per year.

Of course, sheer quantity isn’t everything. What you read matters too, and even if you’re reading excellent books, it’s easy to misunderstand them without careful study.

Still, I found something even more surprising: reading multiple books at the same time also improved the quality of my reading. The program of study at St. John’s is carefully designed. One of the intentions is to juxtapose similar authors and topics at the same time in ways that facilitate understanding.

Partially, this is chronological: for example, you read the Torah before proceeding to read the New Testament and then various Christian theological writers. But you also read across topics in meaningful ways. For example, for my mathematics class, I studied Leibniz’ discovery of calculus at the same time that I was reading his metaphysical works in the main seminar class.

This all affords a kind of reading which Mortimer Adler, author of How to Read A Book, calls syntopical reading, or comparative reading, which aims at a broad, synthetic view of a topic across authors, books, and cultures.

Like most college students, I was also required to write multiple essays at the same time. I was also a prolific writer. One professor said that she would ask for 5 pages and I would hand in 10; that she would ask for oneone essay and get two. In the same way as with reading, I discovered that writing multiple essays at the same time made it easier to increase the overall quantity and quality of my writing.

Since graduating from St. John’s, the biggest influence on how I go about reading and writing has been a pair of online courses: Tiago Forte’s Building a Second Brain (BASB) and David Perell’s Write of Passage (WoP).

Both of these courses borrow key insights from the Theory of Constraints (TOC) and Lean/Just-in-Time Manufacturing. In TOC, small batch sizes, processed in parallel, paradoxically improves the quantity and quality of throughput. This is an extremely counterintuitive finding in manufacturing, the original testbed for TOC, and in some ways it is no less surprising in knowledge work.

The courses gave me a system for reliably producing interesting ideas, and for distributing those in writing. This means that my current intellectual life is increasingly dominated by two forms of knowledge work: reading books, and writing blog posts. From a systems perspective, these can be seen as input and output respectively.

However, having implemented these systems, I discovered a new problem. I had more blog post ideas than I could possibly write. I had a hard time deciding which ones to work on, and began collecting a large number of half-finished drafts of blog posts. Similarly, swimming in an abundance of reading options, I started new books more often than I finished them.

Both problems had a similar flavor: flow problems. How could I be sure I wasn’t abusing massive parallelism, and aimlessly multi-tasking? How could I prioritize what’s most important to focus on?

I found a solution in two key insights from just-in-time productivity: making work visible, and implementing work-in-progress (WIP) limits. I believe Tiago overlooked these ideas when adapting the best principles of TOC and JIT Manufacturing to personal productivity. In this post, I’ll review how kanban, work-in-progress limits, and a lean/agile approach can help knowledge workers produce even more with higher quality.

An Overview of Kanban and WIP Limits

Kanban (which in Japanese means “visual signal” or “card”) was created to solve problems of flow in manufacturing. Kanban has made its way into productivity software like Trello and Notion.

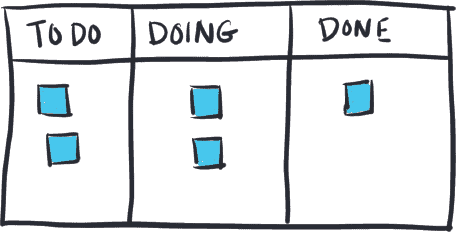

Kanban is a physical or digital board that visualizes work. In its simplest form, it has three columns – Ready, Doing, and Done – with cards (which can be post-it notes, index cards, or digital) in each column to track work.

You can adapt this most basic form to the specific needs of your team, as well as the type of work being done. You can add or subtract columns, and make use of more advanced features, like color-coding, swimlanes, and time estimates.

Regardless of the specific form used, by visualizing the work, you and your team can see the big picture: what work is being done, what isn’t, where bottlenecks are, and what you should do next.

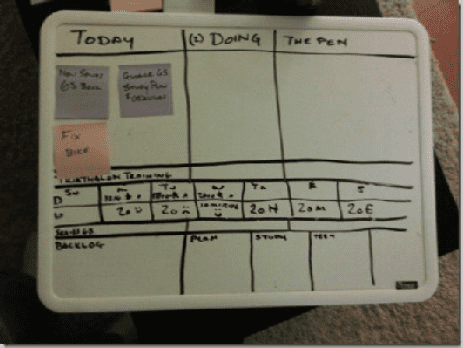

It’s easy to track and manage the flow of knowledge work with a whiteboard, sticky notes, and dry-erase markers, or with software tools like Trello and Notion. Simply making the work visible with these methods will help you do what’s most important.

However, in lean manufacturing and strategy, visualizing the work is just the first step of successful kanban usage. The next step is to install work-in-progress (WIP) limits.

Work-in-progress is all the work that you or your team have started, but not yet finished. For our purposes, that’s a book that you’re halfway through reading, or a blog post that you have a first draft of but haven’t published yet.

Therefore, WIP limits limit the amount of work that can be in process at any time. Rather than starting a new book or blog post every time you feel like it, you try to not do too much at once.

This approximates the focus that comes from, for example, reading only one book at a time. WIP limits afford the focus that comes from processing a limited number of items at a time, and the higher quantity of output that comes from processing in parallel.

WIP limits are usually arbitrary to start: you might limit yourself to reading three books at a time, or to writing two blog posts at a time.

Over time, you can adapt as you understand more about how you work. If you find blog posts tend to go stale in your drafts folder, try lowering your writing WIP limit. If you find you are plowing through books, try raising your reading WIP limit. The most important thing is to limit how much work you’re doing, so that you can finish what you start.

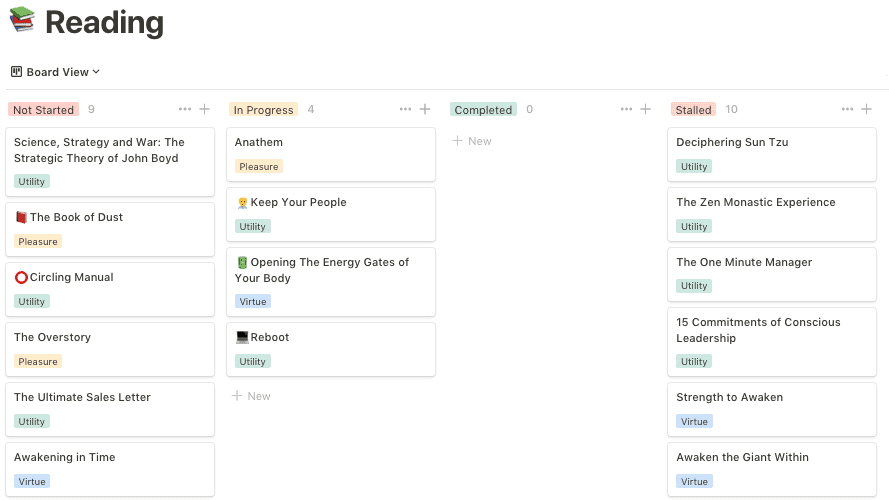

Here are the WIP limits I’m currently using.

Reading WIP Limits

For reading, I am trying to read no more than four books at a time. One of those books is an audiobook. I love audiobooks, but the amount of time I have available to listen to them varies widely. I like having a go-to audiobook to turn to for driving and other similar occasions.

The remaining books can be in any medium (print, ebook, PDF), but should fit into a specific category: a book for pleasure (usually a novel or biography); a useful piece of non-fiction that is relevant to my work or interests; and a book that has lasting benefit, which helps further my character development or meditation practice.

These categories follow Aristotle’s three kinds of friends, a choice that is partially playful – books are a kind of friend, no? – but also practical for me.

When reading these books, I also try to reduce the “batch size,” by ending reading sessions by finishing chapters or sections of whatever book I’m reading. As others have found, it’s easier to pick up a book when you’re starting a new chapter or section.

Writing WIP Limits

For writing, I have a backlog of ideas, posts that I am actively writing, and completed posts.

I use a WIP limit of one post for each of the four categories that I am trying to explore with my writing:

In addition to status and category, I also keep track of several other details, like venue (which blog I intend to publish a given post to); any co-authors a post may have; and reviewers, who I want to send drafts to for feedback.

Of course, I still might write a blog post about an unrelated topic. Or I might think of a post that ultimately proves to be a dead end. But overall, I find that I’m writing more posts, with higher quality and more focus.

Conclusion

WIP limits aren’t for everyone. I shudder to imagine Visakan Veerasamy, for example, one of my favorite internet writers, implementing WIP limits like these. His whole style, I think, benefits from a kind of mood-first productivity.

For myself, I found that WIP limits have helped me to get the best of both worlds – higher throughput from parallel input/output, and the focus that comes from limits. I’ve also found that by experimenting with applying strategy concepts like kanban and work-in-process limits to my personal productivity systems, I’ve developed the intuition needed to apply those ideas to larger scale settings, like the workplace.

If you’re experiencing flow problems like the ones I describe in your reading and writing, or some other aspect of your knowledge work, consider making the work visible and installing WIP limits.

Of course, you’ll need to find WIP limits that work for you – this will be a process of experimentation that likely results in limits that are specific to your needs and constraints.

Whatever WIP limits you install, you’ll find that your system has higher throughput, with improvements in both quantity and quality.

More Resources

- Lean LEGO – The red brick cancer

- Personal Kanban – Mapping Work, Navigating Life by Jim Benson and Tonianne DeMaria Barry (notes)

- Making Work Visible by Dominica DeGrandis (notes)

- Venkatesh Rao’s Now Reading page

- Notion Office Hours with Marie Poulin: Tiago Forte’s writing workflow

Thanks to James Stuber, David Howell, and Cory Foy for their helpful contributions to this post, as well as to Ben Mosior and Cat Swetel for recommending I learn more about kanban in the first place.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- Posted in Guest Posts, Workflow

- On

- BY tasshin