By Tiago Forte of Forte Labs

This post was republished on the Evernote blog. To learn more, check out our online bootcamp on Personal Knowledge Management, Building a Second Brain.

Let’s imagine how you would use Evernote if you had a brain.

I previously explained how the standard tag-based approach basically contradicts everything we know about creativity and how the human brain works.

After a few months of tinkering, I’m ready to attempt an answer to the reverse question:

What would it look like to use Evernote as the basis for a creative workflow, in line with known neuroscience principles?

To answer it, we have to drill down into Evernote’s original mission:

“To give you a second brain”

What does that mean exactly? What, in fact, would we use a second brain for?

I want to dispel a myth: It’s not just “remembering things.” Our brains are not particularly good at that anyway, so having a second one wouldn’t help much.

This includes the storage and retrieval of straightforward factual information: parking tickets, receipts, user manuals, packing lists, recipes, menus, business cards, language materials, doctor’s notes, government documents, tax documents, logins/passwords, school assignments, etc.

This is “dumb” information by design, so an intelligent tool doesn’t add much value.

What the brain does best is thinking. Evernote is most valuable not as a remembering tool, but as a thinking tool.

But this presents us with a tall order. Are we really claiming that a software program can think?

Hope in Cryonics and a Future

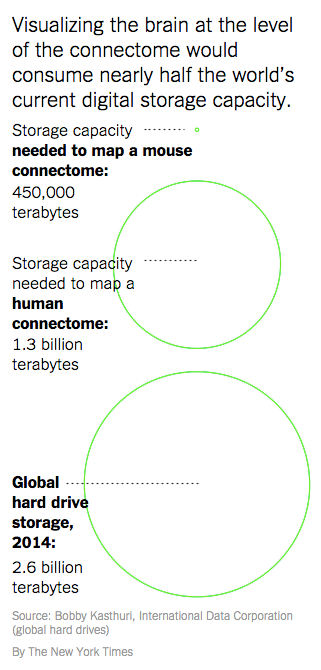

We learned in the New York Times recently that storing a single human brain’s connectome (the complete map of all neurons and the interconnections between them) would take half the planet’s digital storage capacity: 1.3 billion terabytes. In other words, to store just a static map of the physical brain structure of two individuals would require 100% of global storage capacity.

And that’s just the structure, not counting any actual processing. We only have the roughest idea of what that would require, but last year the world’s 4th most powerful supercomputer took 40 minutes to simulate just 1 second of 1% of a brain’s activity. So, we’re not even close.

If a tool like Evernote doesn’t add much value performing low-level tasks like “remembering things,” and it’s incapable of performing high-level creative thinking, what is it good for?

Answer:

Mid-level thinking that interfaces between low-level

memory and high-level creativity, making the

latter as easy, fast, and efficient as possible

To describe what this “mid-level thinking” looks like, we need to dive deep into what creativity means and how it’s enabled.

But let’s not be satisfied with the many books and articles that merely describe creativity in logical circles (“Creativity is seeing things in an original way” Really?!)

We need to answer, in detail: What exactly are the conditions required for high-performance creativity, and how can we use Evernote to create these conditions?

I can think of 5.

1. Promoting unusual associations

It’s been said in many different ways: creativity is connecting things, especially things that don’t seem to be connected.

Nancy C. Andreasen writes in The Atlantic, describing his research scanning the brains of highly accomplished creatives, that “creative people are better at recognizing relationships, making associations and connections…”

Evernote’s ability to capture an extremely diverse range of media formats is a strong hint that this is what it should be used for. It prioritizes this kind of flexibility over speed (it’s terribly slow), collaboration (which usually leads to sync errors), and even stability (it’s one of the buggiest programs of its prominence around).

Scott Barry Kauffman writes in Harvard Business Review: “…increased sensitivity to unusual associations is another important contributor to creativity.”

What better way to increase your sensitivity to such associations than by keeping content from wildly diverse sources in one location?

2. Creating visual artifacts of ideas

Research on cognition has shown that our basic mode of thinking is not abstract reasoning and planning, but “interacting via perception and action with the environmental situation.”

Essentially, it’s easier for us to interact with physical objects in the environment than with abstract ideas in our heads.

Just think of the last time you had to sit down and make a list to “get things off your mind.” Or the last time you brainstormed using Post-Its and suddenly found ideas emerging in the interactions between the pieces of paper.

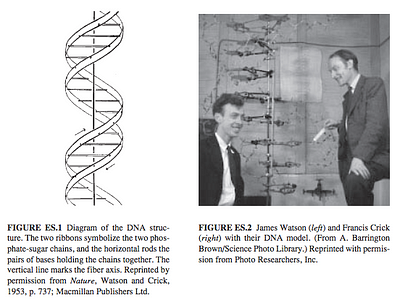

The book Learning to Think Spatially tells the story of how Watson and Crick used this approach to discover the structure of DNA.Although their model had to account for abstract chemical and mathematical observations, they relied heavily on building physical models to arrive at the double helix.

Manifesting their thinking in external structures revealed approach vectors that pure math and two-dimensional diagrams simply couldn’t provide.

By externalizing your ideas in a variety of formats — text, sketches, photos, videos, documents, diagrams, webclips, hyperlinks — you create a system of distributed cognition across “artifacts” that can be moved, edited, rearranged, and combined.

You don’t need “artificial intelligence” to do the thinking for you (the stupidity of even the most advanced personal assistant app is testament to this). You just need visual and spatial anchors for the most advanced supercomputer on the planet — your brain.

3. Incubating ideas over long periods of time

I think one of the least appreciated methods for connecting ideas and producing breakthrough work is the “slow burn.”

Richard Feynman put it best:

“You have to keep a dozen of your favorite problems constantly present in your mind, although by and large they will lay in a dormant state. Every time you hear or read a new trick or a new result, test it against each of your twelve problems to see whether it helps. Every once in a while there will be a hit, and people will say, “How did he do it? He must be a genius!”

Too often, we force ourselves to take an idea from blue sky ideation to practical execution in 48 hours flat. We call it a “rapid prototyping sprint,” and pride ourselves on how little time was spent, as if a new idea is something to be excreted and moved on from as quickly as possible.

But again, this is not how our mind works. I don’t need to tell you anecdotes about how the brain continues working on problems through the night, or as you do household chores, or take a shower, or do grocery shopping. Ok just one: August Kekulé discovered the structure of benzene in a dream.

This post is itself the product of a long, slow burn. It uses 25 direct sources, and many other indirect ones, collected over more than 2 years, but once those pieces were in place, it only took 18 hours to sit down and write.

Think about how much longer it would have taken me to find, read, summarize, and synthesize that many sources, starting from scratch.

Even when we do invest the time, we usually don’t create notes that can be re-used and recycled in other projects. We don’t know what we know, because this information, which we’ve spent precious time and attention to absorb, remains disconnected, fragmented, and scattered. The seeds of insight hide in mysteriously titled folders and documents, opaque black boxes floating in the cloud.

Evernote provides much of the infrastructure for making the slow burn possible. It is durable, universal, centralized, and persistent, increasing the chance that your “dozen favorite problems” repeatedly see the light of day.

4. Providing the raw material for unique interpretations and perspectives

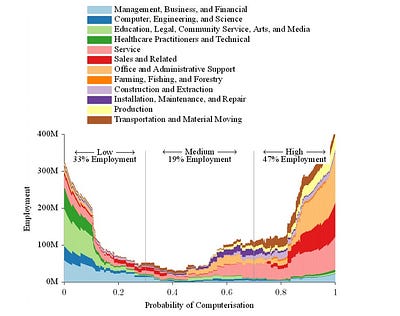

With all the hysteria around machines replacing jobs, there’s one sobering trend that I don’t feel is getting the attention it deserves: increasingly, it is not low-skilled and routine jobs that are being replaced, it is jobs requiring skill, advanced training, complexity, and even human contact.

So much for “more education” being the answer to all our employment troubles.

A big part of the problem is that, as Cal Newport says, “knowledge workers dedicate too much time to shallow work — tasks that almost anyone, with a minimum of training, could accomplish.”

If you work like a dumb machine, your job is easily replaced by a dumb machine.

His solution is straightforward, if not exactly actionable: “We need to spend more time engaged in deep work — cognitively demanding activities that leverage our training to generate rare and valuable results.”

But just try ignoring this “shallow work” (email, meetings, etc.) for a couple days and see what happens.

The solution is suggested by another study, seeking to identify which kinds of jobs best survived the technological replacement of the last tech boom.

What they found was interesting: it wasn’t jobs requiring advanced skills, or comprehensive knowledge, or years of training that fared best. It was jobs that required the ability to convey “not just information but a particular interpretation of information.”

In other words, the jobs that seem to best resist technological unemployment are those that involve building, maintaining, promoting, and defending a particular perspective.

Think of a salesperson citing past results to close a sale. Or a researcher using data to back up their interpretation of an experiment. Or a project manager citing a couple key precedents to support a decision. All these perspectives can benefit from a repository of supporting information.

And here’s where a tool like Evernote comes in. Because defending a perspective takes ammunition.

And by ammunition, I mean examples, illustrations, stories, statistics, diagrams, analogies, metaphors, photos, mindmaps, conversation notes, quotes, book notes — these are the kinds of things you should be capturing.

The more raw material you have to work with, and the more diverse your sources are, the stronger and more original your argument will be.

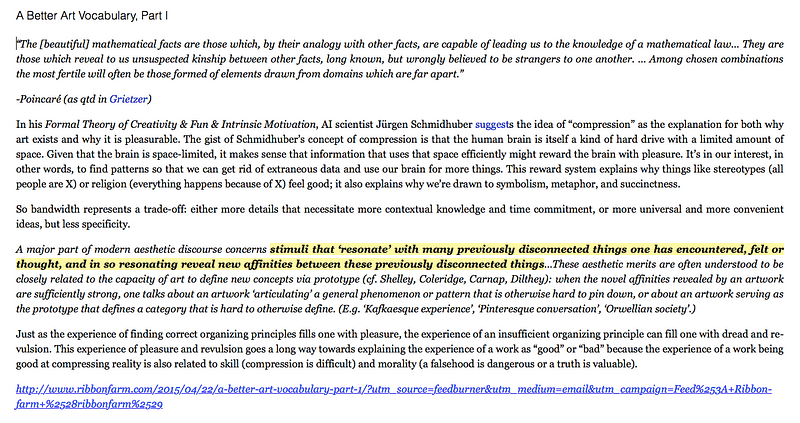

5. Creating opportunities for resonance

The previous point may have left you wondering, “So what does amassing vast amounts of research have to do with creativity?”

First, don’t think quantity, think quality. Again, the design of the app hints at this in multiple ways: upload restrictions, rapidly declining performance when a note gets more than a few pages long, and only 3 possible levels of hierarchy (note, notebook, stack).

Instead, you should pick and choose what you capture very carefully. Think of Evernote as a Cliff’s Notes to everything valuable that you’ve learned in the past — it should include only the key points, not every single detail. Like a cheat sheet for life, but you get somewhere between 60 MB and 10 GB per month, instead of just a 3 x 5″ notecard.

But don’t go to the other extreme, being too picky about what you save. The best rule of thumb is not to set out explicit decision criteria for what you keep. Just thinking about that is exhausting.

Instead, use resonance as your criteria. As in, “that resonates with me.” We know from neuroscience research that “emotions organize — rather than disrupt — rational thinking.” Often, when something “resonates” with us, it is our intuitive/right brain/System 1 mind telling us something is valuable before our analytical/left brain/System 2 mind even knows what’s going on. It’s no coincidence that the former is the same part that drives creativity, spontaneity, and self-expression.

In fact, I very often find that the most counterintuitively insightful pieces of information I save are the ones whose practical application is initially the least clear. My intuition tells me there’s something special about what I’m seeing or hearing, and only much later does the logic become clear.

There’s empirical evidence this really works. From the book Designing for Behavior Change (affiliate link):

“Participants in a famous study were given four biased decks of cards — some that would win them money, and some that would cause them to lose. When they started the game, they didn’t know that the decks were biased. As they played the game, though, people’s bodies started showing signs of physical “stress” when their conscious minds were about to use a money-losing deck. The stress was an automatic response that occurred because the intuitive mind realized something was wrong — long before the conscious mind realized anything was amiss.”

Their conclusion: “Our intuitive mind learns, and responds, even without our conscious awareness.”

This happened to me recently listening to Tim Ferriss’ interview with Brené Brown on vulnerability. I pulled over on the side of the road to take these notes, because they resonated so powerfully with me.

I have no idea what vulnerability has to do with my work on productivity and innovation, but I’m 100% sure I will find a connection eventually.

Misdirected optimization is the root of all evil

Knowing what secondary thinking functions we need Evernote to help us with is a good first step, but since they still require our involvement, we need to perform them as efficiently as possible.

But efficiency is a function of inputs and outputs. So the next question we need to answer is, “What is our most scarce resource?”

Or in other words:

What are we optimizing for?

This turns out to be a fairly profound question, with radical implications for how we organize the information in our lives.

To illustrate:

- If you are optimizing for storage space, you’ll sign up for the cheapest cloud storage service you can find. There are some out there so cheap, it can take them a couple days to retrieve your data if you need it.

- If you’re optimizing for security, you’d better not use cloud services at all, and store your data in encrypted files backed up to RAID 10s. And don’t forget to distribute them to remote bank vaults in case of nuclear attack.

- For comprehensiveness, you hoard every single thing you come across in its entirety, like a digital packrat. These are the people complaining they can’t use Evernote because of the upload limitations (trust me — they are there for your protection).

- For collaboration, you go with a real-time, browser-based editing platform like Google Docs.

- For simplicity, you go with Dropbox, and its Zen no-features-as-feature.

You get the idea.

I use these platforms and many others to store various kinds of information, but there is a reason Evernote is uniquely suited to the demands of creative knowledge work, and continues to be so beloved in tech and startup circles.

It optimizes for the most important metric in the modern digital workplace:

Return-on-Attention (ROA)

The concept of Return-on-Attention came to me as I was wrestling with a different, but highly related question:

What makes one note more valuable than another?

No approach to organizing information can add value without answering this question. A system that doesn’t make distinctions is one that just makes information overload worse.

Many people’s first reaction is to assume that, if the value of information is in its connections to other information, we should label as many of these connections as possible. This leads to the tactic of tagging each note with as many conceivable categories as possible.

But this approach reveals a fundamental paradox: any attempt to increase the value of a piece of information by tagging, labeling, categorizing, grouping, cross-referencing, or otherwise explicitly identifying a relationship of any kind, in reality has the potential of limiting how this information is used.

For example, for the research paper cited above on cognition, one of the most influential works on my thinking, I had the following tags assigned to the note where it was captured:

complexity, cybernetics, decision making, GTD, information management, information overload, knowledge work, neuroscience, notes, optimization, prioritization, problem solving, productivity, project management

At first glance, this seems like a wonderful job I’ve done associating this note with so many categories. But what I’ve realized is that for such an insightful (i.e. valuable) work as this one, these tags represent a constraint on my future efforts to link this information with new and unexpected ideas.

These tags represent, by definition, pre-existing problem frames through which to view this information. Remember our definition of creativity above?

…connecting things, especially things that don’t seem to be connected.

By labeling this note with so many cross-referenced tags, I’m not only locking myself into conventional ways of approaching these fields, I’m creating a false sense of confidence that I’ll be able to find the “right” information when I need it.

In the creativity-driven, exponentially changing world we live in, the opportunity cost of missing a note because it’s “in the wrong box” is simply too high.

But I also couldn’t accept the polar opposite: having no structure whatsoever, letting all the notes slosh around randomly, relying on the magical savior of search to rescue me. There had to be a middle path.

The conclusion I came to was that there is no substitute for the deeply creative act of seeing two puzzle pieces, and applying focused attention to intuit how they fit together. No system can directly replace this kind of thinking through “hard links,” so the only option is to make the process of creating “soft links” on the fly as easy as possible, thus conserving the amount of attention applied.

The Wikipedia article on systems thinking explains why soft systems are preferable to hard systems in this situation. Soft systems are ideal for

“Systems involving people holding multiple and conflicting frames of reference.

And for

“…understanding motivations, viewpoints, and interactions.”

This, my friends, is exactly the work of creativity.

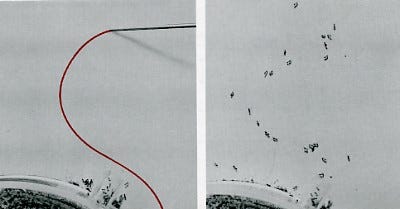

Loading and Unloading

What then is the main cognitive barrier to comparing two ideas? It’s the process of “loading” an idea into your brain. Initially this takes a considerable amount of time, as we consume close to 100% of the material to get the 5–10% (at most) that is actually valuable. The problem comes when we step away from our desks, promptly forgetting (“unloading”) the superstructure of ideas we’re holding in our short-term memory, since we don’t make any effort to preserve the thinking that was done.

This is best illustrated by the experience of putting a complex project aside, and only returning to it months later. The relevant ideas are no longer in RAM, and it takes you a lot of time/energy to get “back to speed.”

On the other hand, think of the immersion you feel after spending a couple solid hours on a problem, where you have all the main ideas at your mental fingertips.

Think about the investment reaching this state of mind entails. It’s not just your years of education and training, your vast store of work and life experiences, the effort of managing stress, nutrition, exercise, sleep, etc. so that you’re functioning at your best. We could consider all that your “administrative overhead.”

What really makes it terribly expensive is the startlingly small amount of time you actually have to focus on deep, meaningful work. I’ve been meticulously tracking my time for years, and I find that I almost never spend more than about 15 hours per week on focused, creative tasks, despite the fact that I work alone.

Returning to Cal Newport: “…Unlike every other skilled labor class in the history of skilled labor, [knowledge workers] lack a culture of systematic improvement.”

And it’s true. If we consider these periods of intense, focused work as our primary asset as knowledge workers, and think about how precious few hours of quality attention we have to spend each week, and how few weeks and years we have on this planet to make something that matters, it is unforgivable that we make no effort to build a knowledge base that appreciates over time. Each day we start again from scratch, trading something invaluable for something merely valuable.

What is the best way to intelligently manage a scarce resource? Measure it.

This realization helped me answer the question of what makes one note more valuable than another:

The value of a note corresponds to how much attention you’ve spent on it

In an economy where attention really is currency, the value of a note is based on how much attention has been invested in it. In the same way that the price of a physical product is based on the cost of goods that have been invested in it.

This in turn suggests an entirely new purpose for Evernote:

A system for tracking how much attention has been paid to a given note

My conclusion was that the global structure of Evernote’s notebooks and stacks is relatively unimportant. I keep notebooks just specific enough to make it obvious where a particular note belongs, mostly to satisfy my spatial itch.

The most salient factor in making ideas accessible for day-to-day use is instead the design of individual notes.

Let me give you a tangible example based on this note:

- I originally clipped this Amazon product page (affiliate link), reminding me that I wanted to read this book.

Almost no attention was spent, so the value of this note was 1 on a scale of 1–10

2. A couple months later, when I had some free time, I read the book, highlighting the parts I thought were most interesting in the Kindle app and exporting them (I use Bookcision for Kindle or the built-in “Share to Evernote” feature in iBooks and Pocket) to the note.

Some time and attention were applied, so its value is now 4, although it’s still too much information to “load” quickly

3. A few weeks later, I reviewed this note and spent some time re-reading my notes, bolding the most insightful and unique sections.

Value now equals 7, as I can much more quickly assimilate the key points by scanning only the bolded sections

4. Some time later, when I started a project drawing on this area, I reviewed only the bolded parts and highlighted (using Evernote’s separate highlighting feature, in yellow) only the very most important parts, leaving me with only 15 highlighted sections from a whole book.

Considerable time and attention has now been applied, and it would be difficult to justify this “expense” if the results of my thinking were not stored in a durable, easily loadable format. Note that as the total amount of content highlighted has dwindled, it has become much easier to quickly grasp its key points, increasing its value proportionally to 10

This note has now become a potent information weapon, its ideas and facts ready to be used in a wide variety of future contexts, at a moment’s notice.

Note Design

What we’re talking about here is putting a lot more thought into the design and structure of each individual note. It is about making individual notes the most prominent actors, like discrete atoms that can be assembled into any form.

Design is always about balancing priorities — in this case: comprehensiveness and compression.

Compression values condensing big ideas into small packages. We gain tremendous value in condensing the Bible (and even whole religions) into the rule of thumb “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Consuming highly compressed ideas is inherently rewarding, because we can feel that each word is rich with substance. It also helps us conserve our precious attention by eliminating the “fluff” (see Derek Sivers’ post on “compressing knowledge into directives” for more examples).

Comprehensiveness values knowing all the facts. It is the voice in your head that says “Prove it.” It wants more data, and examples, and cited sources. It is the fear that you’ll remember the main point, but forget why it matters. It helps us not let anything fall through the cracks, but also drives us toward packrat insanity.

The way to balance these competing priorities is to:

- Progressively summarize the most important points of a source in small stages (compression), and…

- Preserve each of these stages in layers that can be peeled back on demand (comprehensiveness).

Basically, you need to be able to quickly assimilate the main points of a source to evaluate its relevance to the task at hand, while simultaneously preserving the ability to quickly “go deeper” into the source if you judge it to be highly relevant.

But even this “going deeper” must be staged, because you want to avoid creating a black-or-white, all-or-nothing choice between reading just a few key points, or having to go back and re-read the entire original source.

This is the problem with articles summarizing the “actionable tips” from influential books. Without the ability to selectively explore the context of a given tip, it means nothing.

Note: reader Chanmin Woo brought my attention to a great app called Liner (getliner.com), an iOS app and Chrome extension that allows you to simply highlight any passage on a page (which you can then save to Evernote in its entirety). This is a great way to save a specific passage while retaining the context of the page.

Most notes will fall somewhere on a spectrum of relevance, and you want to be able to calibrate the corresponding time you spend “loading” them.

This layering turns a note from a dense, impenetrable jungle into a rocky landscape:

Sometimes you want to do a high-elevation flyover, seeing only the highest peaks. Other times you want to explore the middle ranges by helicopter, perhaps identifying stories or juicy factoids to illustrate a point. And sometimes, you want to parachute in and hack your way through the underbrush, poring over each source and following every rabbit trail.

Designing your note in easily uncoverable layers is like giving yourself a digital map of the terrain that can be zoomed in or out to any level of detail you need. You’re creating an environment in which your “radar” — your semi-conscious, rapid scanning ability to recognize complex patterns and non-obvious connections intuitively —works to maximum effect.

There’s a few key qualities that make this system both useful and feasible:

1. Non-universal

This system is very purposefully not universal. The last thing you want to do is put every single note through multiple layers of compression. That is a terrible waste of attention.

Instead, customize the level of compression based on how intuitively important the source is to your work. I would guess my personal breakdown, with about 2,300 notes, is approximately as follows:

- 1 layer of compression (saving any notes on the source): 50%

- 2 layers (bolding the best parts): 25%

- 3 layers (highlighting the very best parts): 20%

- 4 layers or more (restating the ideas in my own words, applying them to my own context, creating summary outlines, etc.): 5% or less

Although less than 5% of the sources I save go through more than 3 layers of compression, these sources are more valuable to me than all the rest put together.

In general, avoid the temptation to apply the same system everywhere. Not everything needs to scale.

2. Pattern-matching

Our brains far outperform any supercomputer in finding and identifying patterns. You could say our minds are optimized for pattern recognition, which is why we do it quickly and effortlessly.

The note-taking system we create should enable this type of thinking by exposing semantic triggers, not fight against it by burying the most important points in a massive wall o’ text.

Here’s a recent piece by Haley Thurston, where one pass was enough to extract the point:

See how that one phrase jumps out at you, even at this zoomed out elevation?

It will likewise jump out at me if, 6 months from now, I come across this note and need to judge whether it’s worth reading in 5 seconds or less. If the key words in this highlighted phrase match the pattern of the problem I’m working on, I will start by reading the paragraph in which it’s found. If it still matches, I’ll read the rest of the note. If this ends up being a critical piece of the puzzle I’m solving, I’ll click the link and revisit the whole piece. The attention I’m willing to spend has to be justified upfront.

There’s a reason we want to keep all these “layers” within a single note, by the way, instead of, say, creating a master note containing “key points” from various sources: often, the keywords you’ll search for won’t actually be in the “best parts” you’ve highlighted.

A profound quote on productivity very often won’t actually contain the word “productivity.” But the surrounding text is much more likely to contain these “meta-descriptive” words; thus, every word in the entire document serves as “tags” that increase the likelihood of turning it up.

3. Simple

Notice how simple this system is. There are just a few loose formatting guidelines, and only one rule: spend more time/attention on things that interest and resonate with you.

As David Allen says,

Simple, clear purposes and principles give rise to complex and intelligent behavior. Complex rules and regulations give rise to simple and stupid behavior.

There are ways you could make this system more “optimized,” but at the cost of metastasizing complexity. The best system is the one you stick to.

4. Situated

Compressing your notes in this way has an interesting effect: it makes them more valuable to you, but less valuable to others. In other words, this information is highly “situated” in your mental context.

That’s because progressively identifying and highlighting the “best parts” based on an extremely subjective measure like “resonance” has the effect of making the information more legible to you, but less legible to others. You’ll find yourself picking out 2 sentences from a long article, whose relevance is only apparent to someone with your life experiences and “dozen favorite problems.”

Have you ever read a book in which someone else has taken notes? The margin notes either don’t make sense, or their conclusions are totally obvious. Ever-notes are the new marginalia — the personal musings and insights of a unique mind — extracted from paper and indexed for maximum searchability.

This “situated” phenomenon gives rise to a wonderful paradox: I believe my Evernote database is my single greatest business asset, the sum total of my best thinking over years, yet if someone stole it in its entirety it would be of little use to them. This not only is comforting in an insecure digital world, but allows me to do something otherwise unthinkable: share my most valuable notes.

I share them in blog posts (like this one), in projects with clients, and often send them to people I know are tackling a problem for which a source I’ve compressed would be useful. It becomes almost like a personal Wikipedia of learnings I can selectively share to create value for others, while preserving the highest value (the connections to other notes) for myself.

5. Self-Organizing

There’s another, less obvious quality of this system: it is self-organizing.

I said previously that the purpose of Evernote is to “track how much attention has been paid to a given note.” But even this tracking shouldn’t be done explicitly. We humans don’t do well on consistency, thus any system that requires us to use tags to explicitly “track” how much attention has been applied (i.e. Layer 1, Layer 2, Layer 3) is bound to fail.

Instead, use the appearance of the note itself to tell you how much attention has been applied. Just like ants don’t try to remember the path to food — they leave pheromone trails to guide their efforts and others’ — imprint your progress on the terrain itself, allowing your future self to pick up instantly where you left off, whether it was yesterday or a year ago.

In this system, I know that any source with notes attached is at Layer 1, any bolded parts indicate Layer 2, and any highlights indicate Layer 3. As long as I stay consistent with this much simpler and more natural system, I’ll know how much thinking has been done at any point in the future.

Evernote gives us a second brain by allowing us to distribute our thinking across two brains, instead of one. It doesn’t matter that this second brain is nowhere near as smart as your original one — by following the principles of self-organizing systems, you gain the benefits of collective intelligence: “adaptivity, autonomy and robustness.”

In the Flesh

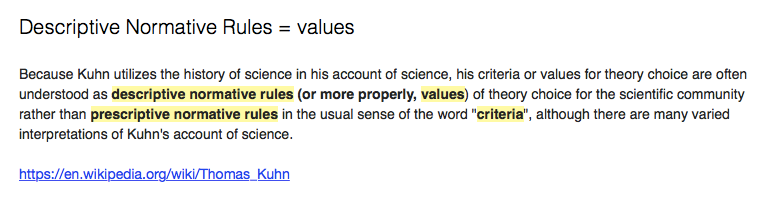

Let’s “compress” these 4 characteristics of our system back into one more tangible example:

That is 1,682 words at Layer 0 (the original article I read), compressed down to 65 words at Layer 1 (my copy-and-pasted notes), compressed to 11 words at Layer 2 (bolded), and 8 words at Layer 3 (highlighted). And it probably makes zero sense to you.

But it makes instant sense to me, because it directly addresses one of my “dozen favorite problems,” a question I’ve been pondering for some time: What are values? Its relevance is fully situated in my mental context.

Reading this paragraph made a lightbulb go off in my head: “values” are “descriptive normative rules,” whereas “criteria” are “prescriptive normative rules.” Not gonna change my life, but it lends just a little extra clarity to my thinking. By the way, look at how many different words in the surrounding text would turn up in a search:

Thomas Kuhn, history of science, theory choice, scientific community, varied interpretations, account of science

Do you see how I would never be able to come up with a universal system of tags or notebooks to describe all conceivable connections?

The Point

I started my career as a productivity coach, giving 1-on-1 advice to help people improve their productivity.

I used to think my job was to give people the “right” productivity tip. I maintained databases of such tips and tricks and hacks, like a pharmacist cataloging elixirs. In fact, this is how I started using Evernote. I was convinced that if I could just give each person the right medicine, I could “fix” their problem.

But over time I noticed something: people fail to be productive not because they lack a critical piece of information; they fail because they don’t see themselves as productive people. It is a self-reinforcing loop.

I realized my role was actually to change self-narratives, to help people design and carry out small experiments in narrowly defined areas to prove to themselves they could believe a different story about themselves. Because once they believe a different story, they have the energy and confidence to seek out all the practical methods and tools for themselves.

I was struck by a recent study, described by NPR’s Alix Spiegel, that illustrated the power of self-narratives: it showed that hotel maids, when informed about how their typical daily movements burned a significant number of calories, actually showed improved blood pressure and weight loss compared to a control group.

It wasn’t that they started working harder: the researchers concluded that their bodies actually changed their functioning in response to the changed perceptions.

Start believing that you’re exercising, even without changing your behavior, and you actually will be. This is exactly what we’re using Evernote for: if you start acting like you are creative, your body and mind will respond, and you will be. Start acting like every idea you come across or come up with has the potential for brilliance, and that potential is more likely to be realized.

Creativity can be practiced. It is a skill that can be improved and cultivated, an acquired taste that increases exponentially in value over time.

And it’s a necessity, not a luxury.

Richard Hamming put it this way:

“I notice that if you have the door to your office closed, you get more work done today and tomorrow, and you are more productive than most. But 10 years later somehow you don’t quite know what problems are worth working on… He who works with the door open gets all kinds of interruptions, but he also occasionally gets clues as to what the world is and what might be important. … [T]here is a pretty good correlation between those who work with the doors open and those who ultimately do important things, although people who work with doors closed often work harder.”

That is next-level productivity right there. Knowing not only how to get things done, but what is worth doing in the first place.

There’s a last quality of self-organizing, adaptive systems, like the one we’re creating here, that I want to highlight: they have the tendency to coalesce around “attractors,” stable regimes of activity that seem to “pull” the actions of agents toward them.

I’ve noticed this phenomenon as a sort of “emergent intelligence” my notes exhibit. They seem to pop up at serendipitous times, to seek each other out across boundaries, to conspire together to push my thinking in certain directions. It’s almost like my Evernote database has its own beliefs, its own conclusions. You could even say, it’s almost like it has a mind of its own.

What’s most interesting about attractors is that they function identically to goals or intentions. They organize diverse means toward coherent ends, creating order out of disorder. In fact, the well-established “order from noise” principle states that the more random variation (“noise”) such a system is exposed to, the faster it will self-organize.

In other words, don’t pursue goals; instead create systems that encourage attractors to emerge on their own. With such a system in place, the more chaotic your environment, the more randomness and uncertainty you are exposed to, the faster you will be propelled to interesting places, as long as you’re open to wherever that may lead.

To learn more, check out our online bootcamp on Personal Knowledge Management, Building a Second Brain.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- POSTED IN: Building a Second Brain, Creativity, Note-taking, Organizing, Productivity, Technology